Wolves in the Wild: What is life like in a wolf pack?

by Scott Dutfield · 29/01/2020

Discover why these animals are nature’s top dog and what it’s like to be a member of the pack

Wolves are one of the most widespread carnivores alive today. Spread across North America, Europe and Asia, grey wolves (Canis lupus) are one of the most adaptable predators on Earth. Also known as the timber wolf, the dominant grey wolf shares ancestors with other members of the world’s many wolf subspecies. It is thought they, along with their cousins the dire wolves (Canis dirus), evolved in Eurasia and crossed the Bering Land Bridge to North America 400,000 years ago.

Wolves are first and foremost carnivores. Equipped with powerful jaws packed with sharp teeth, they have an appetite for large ungulates such as moose, elk and deer. On average, wolves require at least 1.7 kilograms of meat per day to survive but will often feast on around four kilograms when possible. Due to the nature of the preferred meal, this daily diet isn’t constantly supplied. Therefore, wolves go through periods of feast and famine, grabbing their meals as and when they can. As mainly opportunistic killers, wolves may also scavenge the remains of another creature’s kill when hunts aren’t fruitful.

For several thousand years humans and wolves coexisted peacefully. Though the exact time and location is still debated, it’s believed wolves were first domesticated between 10,000 and 15,000 years ago. Both man and beast worked together to form a lethal combination – in a mutualistic relationship, man used wolves to help hunt and for protection, while wolves benefited from easy access to food and shelter. This partnership was so effective some have argued that human and wolf hunting groups may have heavily contributed to the extinction of the world’s megafauna, which occurred around the time of wolf domestication. Since then, after thousands of years of selective breeding, humankind’s historical kinship with wolves has resulted in a huge variety of dog breeds.

However, in more recent times our love of wolves has turned sour. While some wolves are hunted for their fur or as trophies, others are targeted in order to protect our livestock, which would otherwise become easy wolf prey. Continued human persecution has led to some wolf species teetering on the brink of extinction.

Pack life

Like humans, wolves form tight, long-lasting bonds with their relatives

Wolves usually form packs of around six to ten individuals, but this can vary from anywhere between two and 36 wolves depending on birth and survival rates. At the head of the pack hierarchy are the breeding pair, who lead their offspring, and occasionally other unrelated wolves, as a pack.

Past studies had popularised the idea of an ‘alpha’ wolf leading a pack of subordinate ‘beta’ and ‘omega’ individuals. It was thought that beta wolves, the second-in-command, would be ready to step in and lead the pack should an alpha die. These younger members of the pack would also challenge an alpha in the event they become too old or weak. The omegas, it was proposed, were the lowest-ranking wolves in a pack; usually the weakest individuals and those that face the most aggression from those at the top. These studies, however, were based on captive wolves and were not a true representation of wild wolf behaviour.

In reality, the wolf pack family is less hierarchical and behaves more like a human family unit with the parents in charge. That’s not to say there is no intra-pack conflict. Scientists studying wild wolves have witnessed dominance behaviour between adult males of the same pack, where one male would repeatedly pin down another. It is thought that this aggression was between father and son, perhaps a signal that the younger male would soon be breaking away to start his own pack. Lone ‘dispersing’ wolves have been known to travel hundreds of kilometres away from their parental pack’s territory in search of a mate to start a new pack with.

Communication among members of the pack is key to their success. They use three different ‘languages’: sound, including howls, whimpers, and growls; scent, such as scat and pheromones; and body language.

The most well-known form of wolf communication is of course their iconic howl. Howling or vocal communication in a pack can be used for a variety of reasons. Wolves will vocalise to ward off other packs, assert dominance or to assemble other pack members. Howls are also used during pack rallies, where wolves play with and embrace each other to strengthen social bonds. Together, a pack will wander through territories spanning up to 2,500 square kilometres, methodically leaving scent markings to create the perimeter of the pack’s territory and deter other packs from encroaching.

Out of the woods?

Once over-hunted, are wolves returning to their roots?

The original range of the grey wolf has been reduced by around one-third globally. One of the prominent reasons for wolf population decline is the fragmentation of habitats, as it affects their prey species. Disrupting the delicate balance of predator and prey can have dramatic effects on an ecosystem. It works like a seesaw: by removing wolves from one side of the seesaw, the deer numbers on the other side go up. This becomes a problem for the environment the deer live in due to overgrazing. The opposite scenario, where wolf populations increase, is equally problematic, and this is where their conflict with human begins.

When the wolves’ natural food sources run low – either due to disease or as a result of human hunting – they are forced to look for food elsewhere. Wolves will naturally target the weakest and slowest members of a herd, so livestock grazing in fields become easy pickings. This inevitably leads to the persecution of wolves by farmers as they seek to protect their livelihoods. As a result, these canines have been branded as the ‘big bad wolf’. However, when predator and prey populations are balanced they are less likely to cross into human habitats in search of alternative meals.

As human habitats have expanded, wolves’ territories have become increasingly fragmented. Primarily due to the threat they pose to livestock, wolves have faced eradication across North America and Europe, Germany in particular. However, since 1970 legal protection for wolves across the globe has helped combat this decline, and increased conservation efforts are helping to rebuild wolf populations.

However, not all of these projects work as planned. Despite being reintroduced to the east coast of North America in 1987, the critically endangered red wolf (Canis rufus) continues to decline and is predicted to become extinct within eight years unless more is done to help.

Contrary to fairytales, wolves have no interest in humans and will actively avoid us. This makes tracking them an evidence-based endeavour. Using wolf scat, track marks and camera traps, biologists can monitor the population sizes, different packs and most importantly their health, with DNA collected from scat samples acting as a genetic ID tag for each wolf.

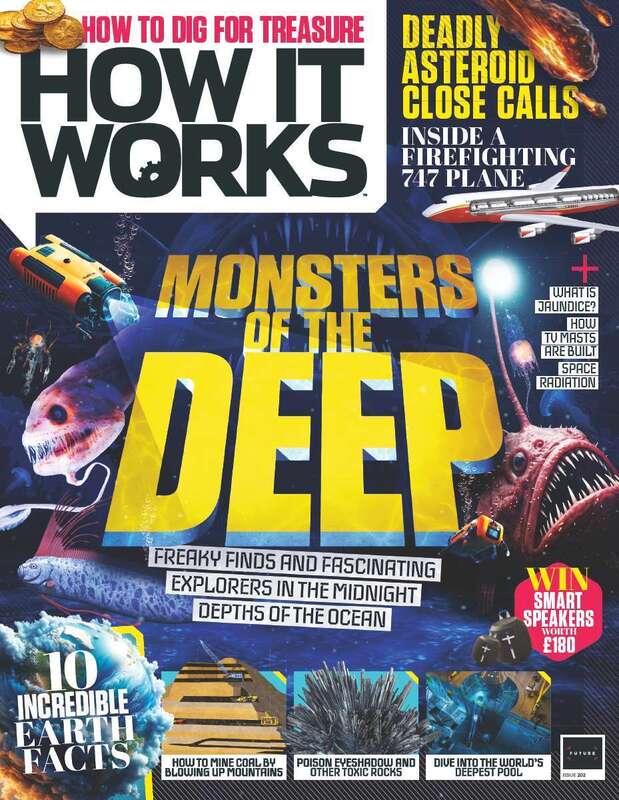

This article was originally published in How It Works issue 116

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!