How technology uncovers the history of the world’s artwork

by Scott Dutfield · 28/06/2020

Meet the art detectives

1. The Element Analyst

A key detective technique, especially when dealing with paint, is to look at chemical composition. To maintain or restore the original appearance of an item, knowing the composition of the paint used enables conservators to perform a composition and colour match for repair.

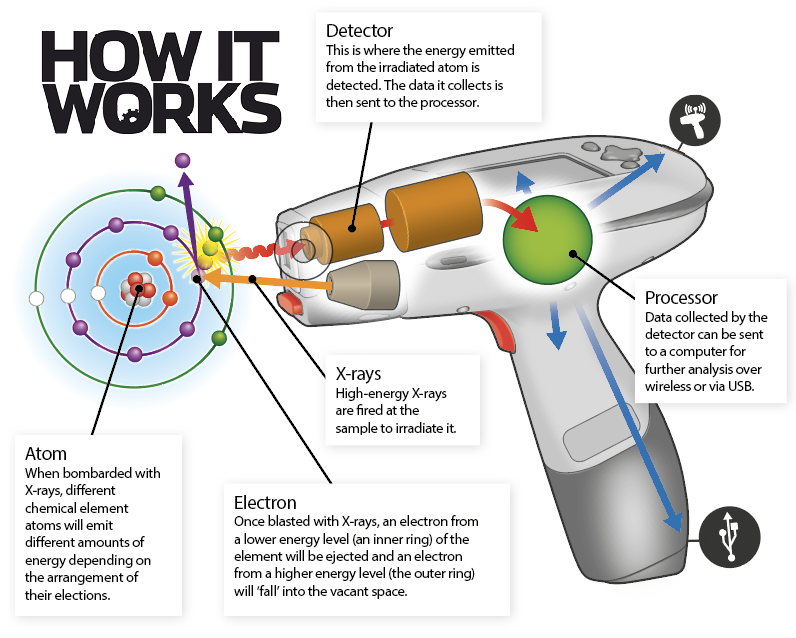

A handheld X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer is just the tool to get the job done. This handheld machine can identify the elemental composition of different materials. This is achieved by measuring the fluorescent X-rays emitted from a sample after it has been stimulated by X-rays emitted from the handheld gun.

Paints contain an array of different elements, such as zinc, iron and titanium. Each of the elements has its own unique signature, which is like its own fingerprint. These spectrometers are used to calculate the unique peak X-ray energy released from the atoms of each element after being blasted by X-rays from the gun. These levels are then recorded as a kind of element line-up, allowing researchers to point out which ones (and how much) are present in any given sample.

This technology isn’t only used to uncover the composition of paints in a frame but also those coating historical machinery. Paul Croft, research fellow at the University of Lincoln, used the XRF spectrometer to colour match the camouflage paint covering a 1943 army tank. While studying a piece of the tank, Croft discovered a high quantity of one element in particular.

“When you understand the make up of paints you can begin to understand the pigments that were used. They were using a zinc-based paint and zinc-based primers presumably for its corrosion-preventative properties.”

2. The Simulator

In order to crack the code of aging artwork, looking to the future can be useful. In lieu of a time machine to hop into the future and see how a piece of art is going to age, artificial aging chambers can provide a glimpse into the future. By exposing materials such as paper and fabric to varying temperatures or levels of humidity, these chambers can replicate the effects natural and artificial environments can have on artwork. This process can be used to explore aspects such as discolouration or degradation. Therefore, conservators can manage the materials, especially the adhesives used to repair different pieces.

“You can look at actual historical materials and see how they age, or you can look at materials you would like to use for a repair and see how they are going to age and if they are going to age similarly to the material that you are trying to repair,” says Dr Skipper.

Discolouration in particular can also be experimented with and quantified using a spectrophotometer. Exposing fabric to natural sunshine can lighten delicate fabrics in paintings or tapestries; these light detectors can graphically represent the level of discolouration to an object, revealing how light may affect original works.

3. The Inspector

In the case of Salvator Mundi, infrared reflectography (IRR) allowed the experts analysing the painting to identify markings made by hand on the canvas. The IRR scans picked up areas where the edge of the painter’s palm had been pressed into wet paint to create softness, which matched a technique known to be used by da Vinci. This advanced technology can essentially dust for prints digitally, and in this instance it picked up prints that were over 500 years old.

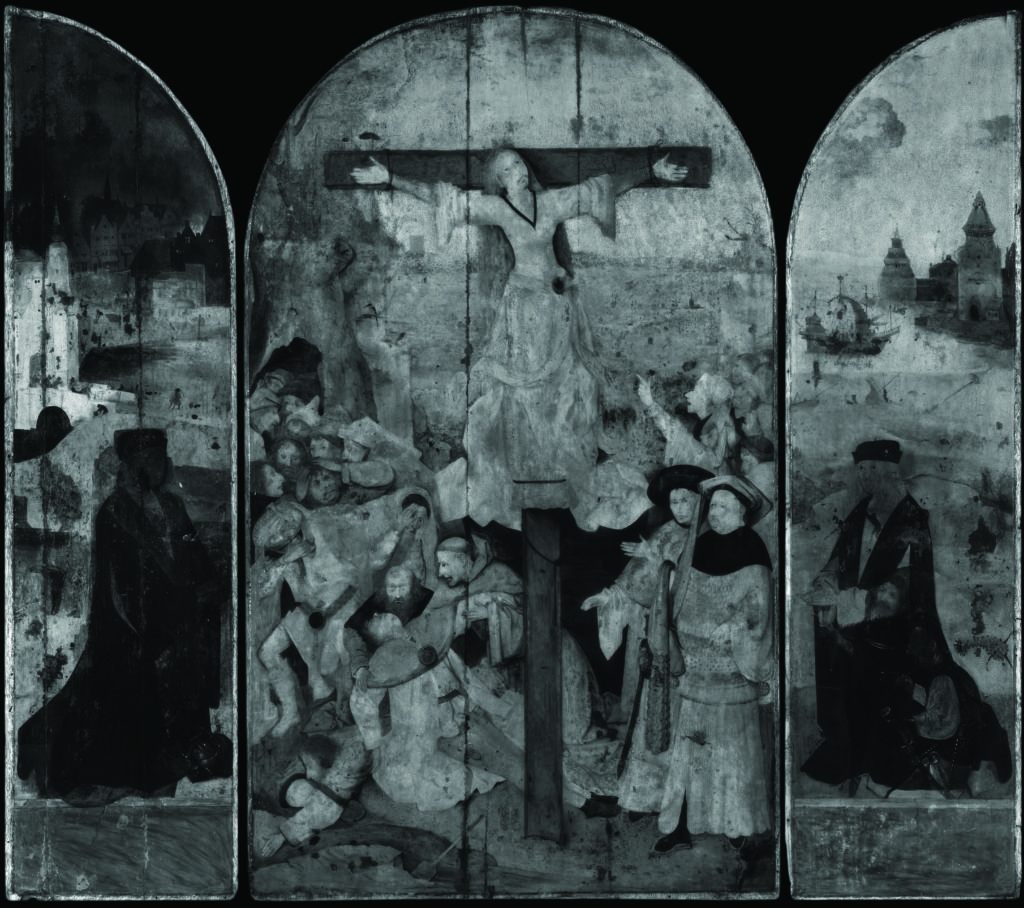

In most cases IRR is used to reveal work that has been previously hidden by another layer of paint. This piece of technology uses infrared light to look beneath the surface. Visible light is absorbed and reflected from the surface of objects, while infrared can penetrate past the top layer of paint before being reflected, reaching the ground work of a painting. The reflected infrared can then be recorded and images of drafts, mistakes, a change in scenery or hidden figures can be brought to light.

4. The Radiologist

In order to create a full picture of an artwork’s past, sometimes you literally have to take a look inside. Taxidermy, for example, is an art form commonly under this type of investigation. Without slicing into animals again, computer radiology uses X-rays to establish the way the specimen was prepared and therefore how best to fix damaged items. In exactly the same way as a person may have to get an X-ray for a broken bone, radiographs emit X-ray radiation to penetrate the skin and produce a contrast image of the inside of the body. This can then be used to create a digital image, rather than developing a film. The approach allows for the identification of any metal armature or bones. The technique can also be used on ceramics and to identify hairline fractures, for example, which may remain undetected until X-rayed.

5. The Dissector

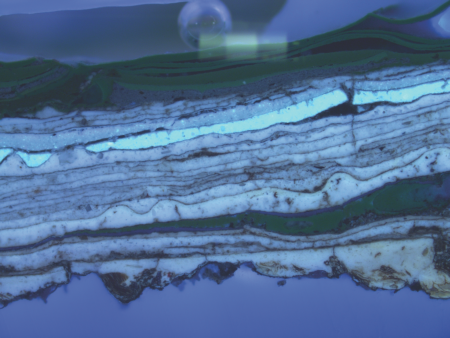

You should never judge a book by its cover – equally, you should never judge paint by its colour. Hidden beneath the top layer of paint can lie several layers of previous paints, representing a timeline for each piece. With the use of optical microscopes, these art detective technologies can reveal the different pigments, dyes and layers of a single sample of paint.

Samples from paint covering a gilded frame, for example, can be taken and manipulated to sit up at a right angle to expose its layering and then held in a block of transparent resin, which is similar to the way in which prehistoric insects are found encased in amber. Placed under a microscope, these samples can reveal the different coatings the object being investigated could have been covered in.

Paul Croft uses this technique to highlight the contrasting layers of traditional oils and modern paints within some paintings. The different layers glow when viewed under ultraviolet light. “All of those early layers that fluoresce, those are the traditional oil paints, and those that don’t are the modern synthetic paints,” explains Croft.

Different paints will have been applied at different times, so by comparing the paints to those in historical records, these layers can uncover the story of the artwork’s journey over time.

This article was originally published in How It Works issue 111

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!