All About Snakes

by Scott Dutfield · 25/10/2018

Slither this way to learn everything you need to know about these stealthy serpents

In general, snakes get a bad rep. They are animals that are traditionally treated with suspicion, as sly and cunning creatures. The truth is, they are both those things. But they’re also remarkable animals with amazing defences and incredible adaptations. Their ability to be some of the scariest animals on our planet without even having legs is no mean feat! It’s not clear exactly when snakes evolved in their current form, but scientists do believe that their ancestors were four-legged, lizard-like creatures. A fossil dating back 113 million years is thought to be the most primitive ancestor of the modern-day snake, and has a serpentine body but with the addition of four tiny legs. From these humble beginnings, snakes have conquered most environments on Earth, and range from the colossal, water-dwelling, constricting leviathans – such as the Amazonian anacondas – to the tiny, noodle-like threadsnakes.

The UK has only three native snake species, and the adder is the only venomous variety. This snake lives in rough, open countryside, but there’s no need to worry – it’s pretty shy, and no one has died from an adder bite in more than 40 years. Snakes have an affinity for water, and all snakes can swim. Some species are better at underwater life than others, such as sea snakes that can stay submerged for an hour or more. Despite their aquatic surroundings, these snakes can’t drink seawater, and can go for months without drinking fresh water. It’s proposed that they rehydrate with fresh water when heavy rains fall over the ocean. The majority of snake species aren’t venomous, but for those that are, this is as much of a defence mechanism as it is a hunting tool. Each venomous snake species has its own special toxic cocktail of venom, containing a mix of proteins and enzymes designed to immobilise both predators and prey. Some venom works by attacking the nervous system; others by causing viscious damage to blood and tissue. Some species (including vipers, pythons and boas) even have a superpower. They possess a sixth sense: the ability to detect heat signatures and see in infrared. This, coupled with their supreme strength, agility, venom and lightning fast reflexes, means that a snake’s prey doesn’t really stand a chance.

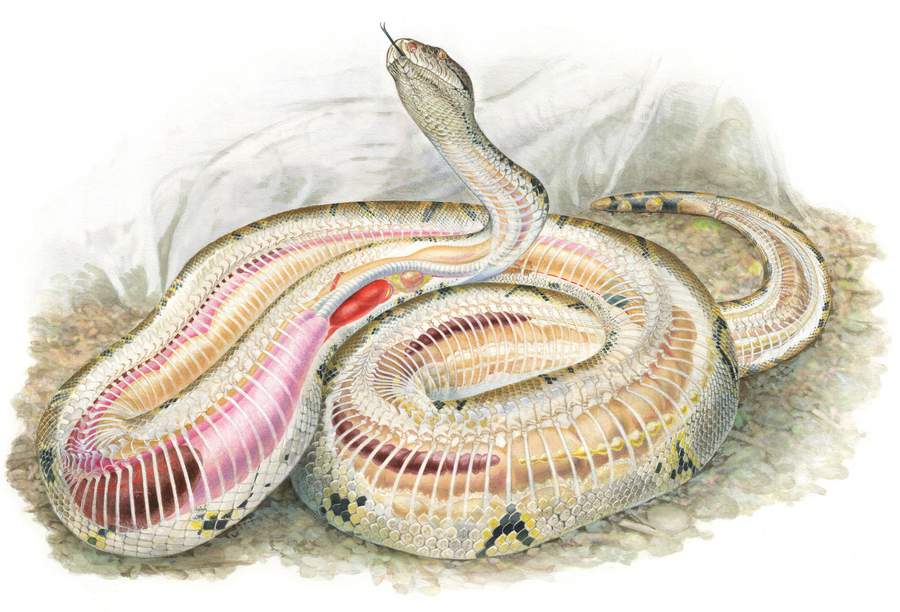

Inside a serpent

A snake is essentially a long bag of stomach and muscle, and much of a snake’s internal features are focused on its ability to eat really large items. The ribs are flexible to allow for expansion, and the heart is free to move (as there is no diaphragm) so that it doesn’t get damaged when the snake forces a large meal down the oesophagus. A snake has small scales on its back and sides, and wider ventral scales (on the underside) that perform like treads on a tyre. The large plates enable the snake to grip the ground while its powerful muscles propel it forward.

- Eyes- Snakes have no eyelids. Instead, each eye is protected by a transparent scale, known as a spectacle.

-

Gall bladder- Bile from the liver is stored here and released into the small intestine when it is needed to break down food.

-

Intestines- These long, narrow and coiled tubes are where nutrients from snakes’ meals are absorbed.

-

Thyroid gland- This gland secretes essential hormones. It’s thought that it has a role in shedding and growth.

-

Heart- A snake’s heart has just three chambers, yet it still functions like a four-chambered heart.

-

Vertebrae- Dependent on species, snakes have 200-400 vertebrae along the length of their bodies, with a pair of ribs attached to each one.

-

Liver- This is the snake’s largest organ. Among other functions, it processes waste, and excretes bile and digestive enzymes.

-

Lungs- Most snakes don’t have a functional left lung, and their right lung is much larger in order to compensate for this.

-

Skin- Scales of snakeskin are dry, despite looking slimy. They are made of keratin, the same substance as in human fingernails.

-

Kidneys- Like mammalian organs, a snake’s kidneys filter the blood and remove waste products.

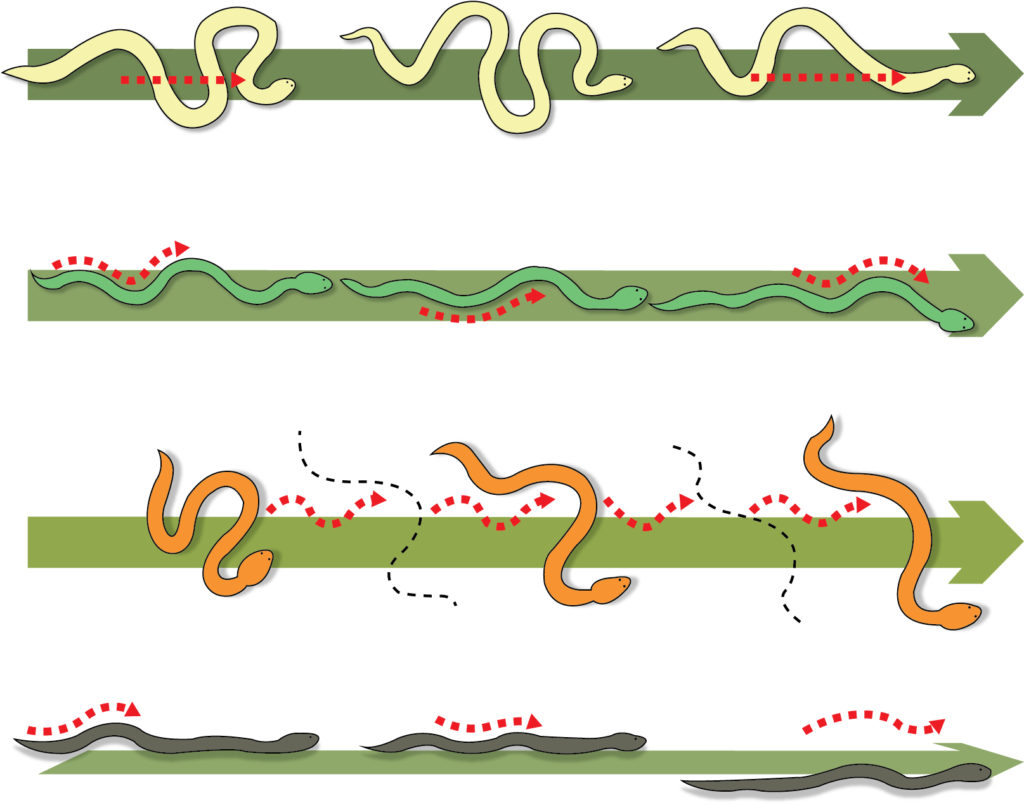

How snakes move

1. Concertina- The snake pulls its body into alternating bends to grip on, and then moves forward at it stretches out – a method often used for climbing trees.

2. Serpentine- The fastest and most common method that looks like ‘slithering’, the head moves side to side, and the body follows, pushing off the ground as it bends.

3. Sidewinding- Used where there is nothing to grip on to, such as sand, this method involves the snake making an S-shape and throwing its body sideways across the ground.

4. Caterpillar- Also called ‘rectilinear’ motion, this is where the snake moves just like a caterpillar, creating waves with its body up and down instead of side-to-side.

Teeth & Venom

A fearsome part of every snake is its teeth. Here’s the lowdown on those serpentine pearly whites…

Snakes swallow their food whole, so their teeth aren’t used for chewing, but the dentition that a snake sports is often determined by the way it hunts. Regardless of type, snake teeth are all backward-curved, which is a handy adaptation to help the snake secure its quarry. There are three types of snake teeth: first up are the sharp yet even teeth that don’t deliver any kind of venom. These belong to non-venomous snakes, such as boas and pythons. Snakes with prominent fangs come in two types: grooved and hollow. The former is more common and, as the name suggests, they have a channel down which venom is delivered. These can be found at the front of a snake’s mouth – think of the terrifying ‘smile’ of the king cobra, complete with incredibly sharp weapons ready to strike. But they can also be found at the back of the mouth, like in the hognose snake. Rear-grooved teeth mean that

the snake has to force prey to the back of its mouth to dispense venom. The hollow-fanged snakes include vipers and cobras, some of the most deadly serpents. Their prominent fangs have tubes through which venom flows, directly entering prey from syringe-like teeth to do their deadly work. These fangs often fold in against the roof of the snake’s mouth until the opportune moment to strike. Fangs are attached to venom sacks behind the snake’s eyes. The venom is delivered as muscles in the snake’s head compress the sacs to administer a noxious dose.

5 of the most dangerous snakes

-

Inland taipan- Found in the semi-arid bush of eastern central Australia, the venom of the inland taipan is by far the most toxic of any in the world. However, unlike its aggressive cousin, the coastal taipan, this snake actually shies away from humans.

- King cobra- This is the longest venomous species, and to add extra menace to its crippling venom and huge fangs, it can raise a third of its body into the air and fl are its hood. A single bite can kill an elephant.

-

Saw-scaled viper- One of Asia’s most dangerous snakes, its venom isn’t as toxic as other species’, but this snake lives in populated areas and is quick to bite if it’s feeling threatened.

-

Boomslang- Once thought to be harmless, this rear-fanged snake actually has potent venom, although it is generally a placid snake. It is a tree dweller and lives in sub-Saharan Africa.

-

Black mamba- This snake is brown in colour, and gets its name from the colour of the inside of its mouth, which it displays when threatened. It is Africa’s longest and one of the world’s fastest snakes.

This article was originally published in How It Works issue 90, written by Ella Carter

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!